Lin-Manuel Miranda

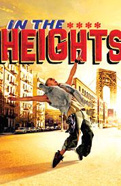

Lin-Manuel Miranda is wired. He has just come off of doing a matinee of his new Broadway musical In the Heights for a swarm of enthusiastic high school students and then squeezed in a meeting about the upcoming cast album. It's easy to believe him when he tells a story about a cross-country trip where he was “kept alive by Red Bull and freestyling.” Freestyling, an improvisational form of rap, is a big part of Miranda's musical valentine to Upper Manhattan, as are several types of Latin music, a healthy dose of hope and a singularly New York angle. Miranda still seems awed by how far his little side project from college—the highly competitive Wesleyan—has come, and his excitement even spills across over the phone. “I never thought I'd be talking to you from the stage of the Richard Rodgers Theatre, which is where I am right now,” he exclaims at one point. We checked in with Broadway's adorably frenzied new star, and perhaps more importantly, new songwriter, soon after In the Heights opened on the Great White Way to chat about inspiration, critics and being a bored little kid.

I was looking at our Photo Op of your opening night, and there were so many emotional faces on stage. How did you feel finally opening on Broadway?

Surprisingly little was running through my mind. My overall goal was just to stay on top of it—stay on top of the emotion of the audience. Everyone in that audience was someone who loved someone on stage—that's what opening nights are. During the last number, it was occurring to me that I have spent my adult life writing this show. I started writing it when I was 19 years old, and I just turned 28.

Can you believe that you can stop tweaking it now?

I can't believe it, actually. It's an enormous sense of relief. It's done; we're open. We did it!

What part of the show that you wrote when you were 19 is still in the show we see on Broadway right now?

Exactly five notes. “In Washington Heights!” That is literally the only phrase that survives, though there are chord progressions throughout that have survived. The musical themes of the show evolved pretty early, and we've been playing with permutations of them for years. But I've cut maybe 50 songs, or versions of songs, from the show.

It was one-act. It was this love triangle between Nina, Benny and a brother Nina had named Lincoln. Nina's brother was secretly in love with Benny. Most of the characters were there. Nina's parents were prominent, [Miranda's character] Usnavi was there—he was sort of comic relief. Vanessa was Nina's best friend. We didn't put in the salon yet, and Abuela wasn't there, but Benny's mother was a major character who was sort of estranged and he reunited with her at the end of the old version. It was completely different. We just sort of took those characters and wrote a new show with them.

Tell me about the various styles of music represented.

Oh, it's such a gumbo. I don't think the average theatergoer knows how many different types of Latin music we're representing. They see the broad strokes. They see that Usnavi speaks in hip-hop, and when we hear from the Abuela, we hear Cuban mambo. “Carnaval” is a mix of a Puerto Rican plena and other Mexican types of music; it's like a pan-Latin folk tune. Vanessa sings a Dominican merengue. Every character speaks in their homeland language.

I assume that as a member of the creative team, you've had a chance to see the show, despite the fact that you star in it.

I've been able to swing out three times and watch the show. It was insanely helpful. I have a fantastic understudy named Javier Munoz; he's in the ensemble, as well, and he's great. When you see him perform, you see the piece really clearly.

How did it feel to watch In the Heights?

It's a thousand times more stressful then being in it, strangely. I think it's that feeling of you don't have any control. When I'm Usnavi, I set the tone to a degree—at least I can control my track and my little corner of the world. To sit back and watch it is scarier.

How do you keep the writer part of yourself out of your head when you're on stage?

Oh, there's so much other stuff to think about, particularly when you're dancing Andy Blankenbuehler's choreography. We are moving every moment and it's very precise, so if I start thinking, “Hey, maybe this line could be better,” someone's foot is going to clock me in the face.

How close is the cast?

Let's just say there were 22 of us sharing two bathrooms off-Broadway. In that kind of situation you can go two ways: You can kill each other, or you can say “We're family.” And that's the way we went. We have, I think, 11 Broadway debuts on that stage, including my own. So everyone completely has a sense of how special and how rare it is to come to Broadway with a show that is such a labor of love. I didn't even write this show for course credit [at college]. I wrote it because I needed to write it. It was the closest thing to “possession” I've ever felt in my life.

What was the moment of inspiration for you?

There were several. I originally had Nina at Yale instead of Stanford, and I think her first lines were, "Waiting on the Metro-North train, I am going insane, waiting in pain for it to take me home." I had stayed with my high school sweetheart through the first two years of college, and when I was a senior [at Hunter High School] and she was at Yale, I would take the Metro-North train up to see her on the weekends. You could see that the schism between rich and poor that is very pronounced in New York is also very pronounced in New Haven. And you can see all of it on that Metro-North train. It was the first Latin-sounding song I ever wrote.

If you could go back in time and talk to your 19-year-old self, what would you tell him?

It's funny you mention that, because there is a new song in Act Two called “When the Sun Goes Down.” I watched the show for the first time three weeks ago. And I'm fine watching my show; I don't get emotional. But when they started singing that song, I started bawling like a little girl lost at the mall.

Why?

I think it has a lot to do with the fact that when I wrote the first draft of this show, my high school sweetheart was going abroad to study. It was our first major amount of time apart, and I wrote it all in that winter break when she was gone. I was lonely and I missed her, but I also thought that we weren't right for each other. I was scared to say it, and all the angst and the mixed emotions were the emotional energy that went into that first draft. When I saw “When the Sun Goes Down” three weeks ago, I realized that this is the song we should have sung together when we were kids. It's sort of like, “Who knows what the future holds, but we have this summer.” So I would have sent that song back to the 19-year-old and said, “It's OK if you're confused.”

I did. I think if I were an actor just for hire in a show, I probably wouldn't read the reviews because what can you do? I'm wearing several different hats in this show, so I have a lot at stake with reviews and they carry a lot of weight. I treat reviews the way I treat notes: You read them, you go to sleep, and you forget about them. If something makes your stomach hurt in the morning, then maybe there's something to it—or maybe not. It's one person's opinion, and that's all it is.

The reason I ask is that some critics think the show should be grittier, and I wonder what your response is to that.

I'm not surprised, given the media's perception of what Washington Heights is. You see it in movies—with notable exceptions in recent years—as the drug deal place. That's where they go in American Gangster to process the coke, and it's the drug scene in Shaft. So I'm not surprised by that. At the same time, I also wonder what show they're watching. At the end of the show, there's no real happy ending. This isn't Much Ado About Nothing.

What do you think when you hear this show being hailed as the first truly Latino Broadway musical?

I think it's an honor. I think the writers of Zoot Suit were Latino, but I didn't know about that when I was a kid. I knew about West Side Story, which I loved and I think is a masterpiece. Then there was Capeman my senior year in high school. I saw it three times in previews, and it broke my heart because I think Paul Simon's music was really gorgeous.

When I saw the show, there was a very young—and vocal—audience there. What does it feel like to hear such exuberance from the stage?

It's the most rewarding experience in the world. We just did a kids' matinee. I literally say, “Glorious little place in the Caribbean, Dominican Repub…” and you can't hear the rest of it for a good few bars because everyone just starts screaming. “DOMINICAN REPUBLIC!”

It's amazing to think that this might be their first Broadway musical.

I think it is so enormously validating to see your culture on a stage. This is the show I would have lost my mind if I saw it when I was a little kid. When the kids screamed today—I wish I could bottle it for a rainy day. It's amazing how hungry these kids are to see themselves represented in a way that's even close to accurate.

I saw the video of you singing and dancing your heart out at eight years old on YouTube. I imagine that's who might have been in your audience today.

Yeah, it was the high school version of that.

You must have been a really creative little kid.

I was the most bored little kid you've ever seen. The sad thing about that YouTube video is that I have hours of video like that. I have GI Joe fight scenes that were animated. I did stop-motion and Harryhausen animation. I thought this was compelling, but it was only compelling to me. I have hours of C3PO fighting against Stormtroopers. Literally, in stop motion, like I'd stop the frame, and move them a little bit… and I have reams of flipbooks. And my homework sat with dust on it in the corner. That's just the kind of kid I was. That's the kind of kid I am.

How have your parents reacted to the success of In the Heights?

They're very proud I found an outlet where I can earn a living and have an apartment and actually live out the sort of insane notions that I've been trying to get them to watch since I was a little kid. My parents both really fell in love with musicals at a young age, too. My dad romanced my mom with “Impossible Dream” from Man of La Mancha and my mom—every time she hears “Bring Him Home” from Les Miz, she starts crying. I knew what the power of musicals was when I was really young because I saw how it affected them.

What was the first musical you saw?

The first musical I saw was Les Miz, and I fell asleep. I was in second grade; I don't remember it. I remember [my parents] bought the cast album, and I promptly memorized every song on it—imagining backbeats over “One Day More” and stuff. The musical that really grabbed me was The Phantom of the Opera. At the end of the day, that show is about an ugly songwriter who can't get girls to notice him, and I really responded to that. I was like, “That's about me!” I was just hitting puberty when I saw that, it couldn't have come a moment too soon. It changed my life.

Yeah, and I think that's great! I think a musical has done its job if you're doing something in life, and it reminds you of a song from a show because then something's been reflecting reality. I went on a cross country trip to Vegas with some friends—I had never really seen the middle of the country before—and I remember singing “There's a bright golden haze on the meadow” in the middle of this field in Iowa. I was just like, “Oh! That's what he meant when he wrote this song!” I think if someone goes up to Washington Heights and they see a piragua guy and they start singing “Piragua” to themselves, I've done my job.

You don't live in Washington Heights, right?

I don't. I live in Hell's Kitchen or the Upper West Side—I don't know where I live. I live surrounded by car dealerships.

But you still spend time up in the Heights?

I do. My girlfriend lives in Washington Heights, and my parents are in Inwood. I spend half my week up there.

How did you start freestyling?

I never did it as a kid. In high school I had friends who were really good at freestyling, but I would just beatbox because I was too intimidated to do it. I liked to go home and write. Then I started doing it in college for fun: You're drunk and you start making stuff up. My brain is always wired to lyrics.

And now you do it with a group, Freestyle Love Supreme.

It's a hip-hop improv group. We started doing it really as therapy; we'd literally make up rap versions of our day. [It began as] a fun thing to do on the side, but we've been to all the major comedy festivals in the world. Tommy [Kail] the director of In the Heights, came up with a great structure for it. We ask for a verb, and the verb becomes the first song of the night. We do current events and whatever the audience throws at us.

What are some of your favorite rhymes in the show? As someone who can freestyle, you must have one that you're really proud of in there.

Oh, I have lots that I'm really proud of. There are lots of homages throughout the whole thing to different rappers that I like. For instance there's a section in the new “Carnaval,” where he goes “Maybe you're right Sonny, call in the coroners. Maybe we're powerless, a corner full of foreigners. Maybe this neighborhood's changin' forever, maybe tonight is our last night together, howEVa!” That “howeva” is me doing my best Jay-Z impression. That's a very Jay-Z-inflected line. Then there's, “It's silly when we get into these crazy hypotheticals,” that's me doing Big Pun because Big Pun used to just load—l mean literally every sixteenth note was a different syllable. I'm just trying to do this mash-up of my favorite rappers, and what's really fun is also assigning different rappers to different characters. It's fun not only to play with the world of hip-hop but then apply them to musical theater. It's so perverse.

What's the best part about getting on stage every night?

There are a million things I love about it. I think about this performance as a celebration of the eight years I put into it. It's like I built this really cool car, and I get to drive it every night.

See Lin-Manuel Miranda in In the Heights at the Richard Rodgers Theatre.